Librarians and archivists measure a collection in ‘linear feet’: the length of front-facing shelf space the volumes and records occupy. I take my materials very seriously and am on a lifelong quest to organize them correctly. (Efficiently? Thematically? Delightfully?)

My home studio is banded by reclaimed wood that I arranged into a DIY wall-to-wall library unit providing roughly 51 linear feet of shelf space (and room for three desks). It’s a lot for one room in Brooklyn—and not enough. I moved more than a dozen bins to a storage unit. And still, books and reference material pile up around the house. So, late last year, I admitted defeat and installed more shelves in the studio. Thus opening up another 18 linear feet.

Now, there is room to breathe again. To rethink the groupings.

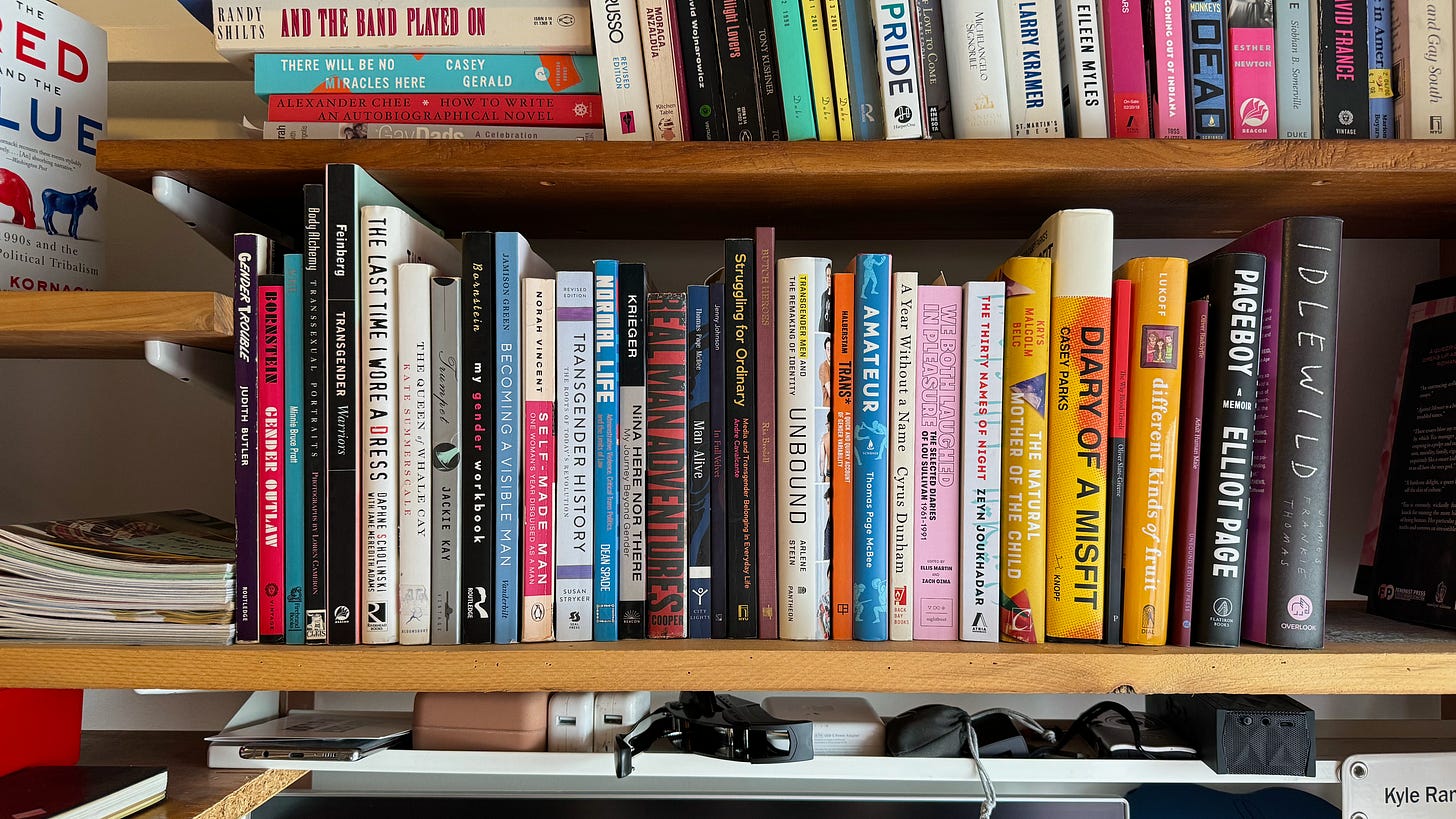

To kick off this new project examining my (our? many?) transmasculine experience(s), I pulled all of the relevant titles from my library onto one shelf right above my standing desk. Exactly where the light comes through the window, this shelf is a version of my undergraduate fantasy to have an assigned library carrel deep in the stacks—long before a smartphone and parenthood—where one could study quietly for endless hours.

Twenty-eight titles, for now, are arranged chronologically. (With a stack of Original Plumbing zines functioning as a bookend.) Just about 1.75 linear feet. The collection spans more than three decades of publishing and over 100 years of transmasculine history. A wide range of genres are represented, including memoir, poetry, fiction, reported narrative nonfiction, photography, edited personal journals, and academic theory. Not all of the books are written by self-identified transmasc authors, though most are, and all of them touch on the topic in some way. A few are written by trans femmes (e.g., the legends

and ).1Touching each of the books, gathering them together, feels ritualistic. Magical. My heart swells thinking about suburban teenage me venturing off to the city (Washington, D.C.) in the 1990s to try and find the few trans books stocked at the gay (Lambda Rising) or lesbian (Lammas) bookstores. There weren’t many options then. I had the courage to buy books like Kate Bornstein’s inclusive My Gender Workbook or Judith Butler’s academic Gender Trouble and was far too terrified to purchase Loren Cameron’s provocative Body Alchemy, which portrayed actual trans bodies.2 So many memories are contained on one shelf. I remember being confused and yet captivated by Norah Vincent’s experiment in living as a man (while explicitly not identifying as trans) in Self-Made Man. My former college roommate’s book of poetry is here. And I found a dear friend in Nick Krieger after reading his memoir Nina Here Nor There.

Now that the spines are all aligned, I can more clearly see what’s absent. My weathered copy of Stone Butch Blues is glaringly MIA and should probably be replaced. I never did buy Max Wolf Valerio’s The Testosterone Files, but I read a library copy. While the collection reaches from 1990 to the present, there are years not represented when I was likely pulled in other directions. (Like becoming a father.) And this exercise prompted me to order a few more, such as Harry Nicolas’ new memoir A Trans Man Walks Into a Gay Bar.

The most recent edition to my collection is

‘s Adult Human Male—a selection of exceptional essays published late last year.3 Oliver writes searing sentences with enviable clarity. I underlined something on nearly every page. In an essay entitled “Second Act,” Oliver explains the trans visibility paradox:The frustrating by-product of using invisibility as a survival tactic is that we leave little trace of ourselves for other people to find, which adds to the mistaken belief that we’re a relatively new and rare phenomenon.

This library collection serves as proof of life. We exist, we have existed. We will continue to.

xx

Kyle

A transmasculine library (as of Jan 13, 2024)

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. 1990.

Bornstein, Kate. Gender Outlaw. 1994.

Cameron, Loren. Body Alchemy: Transsexual Portraits. 1996.

Scholinski, Daphne. The Last Time I Wore a Dress. 1997.

Summerscale, Kate. The Queen of Whale Cay. 1997.

Kay, Jackie. Trumpet. 1998.

Green, Jamison. Becoming a Visible Man. 2004.

Vincent, Norah. Self-Made Man. 2006.

Stryker, Susan. Transgender History. 2008.

Spade, Dean. Normal Life. 2011.

Krieger, Nick. Nina Here Nor There. 2011.

McBee, Thomas Page. Man Alive. 2014.

Johnson, Jenny. In Full Velvet. 2017.

Cavalcante, Andre. Struggling for Ordinary. 2018.

Brodell, Ria. Butch Heroes. 2018.

White, Arisa. Unbound: Transgender Men and the Remaking of Identity. 2018.

Halberstam, J. Jack. Trans*. 2018.

McBee, Thomas Page. Amateur. 2018.

Dunham, Cyrus. A Year Without a Name. 2019.

Martin, Ellis. We Both Laughed in Pleasure. 2019.

Joukhadar, Zeyn. The Thirty Names of Night. 2020.

Belc, Krys Malcolm. The Natural Mother of the Child. 2021.

Parks, Casey. Diary of a Misfit. 2021.

Slate-Greene, Oliver. The Way Blood Travels. 2021.

Lukoff, Kyle. Different Kinds of Fruit. 2022.

Page, Elliot. Pageboy. 2023.

Thomas, James Frankie. Idlewild. 2023.

Radclyffe, Oliver. Adult Human Male. 2023.

Have a book (or writer) to add to the list? Please suggest in the comments.

Other transfemme-authored books live in my library but their specific topics fall outside this current focus on transmasculine folks. Drawing any boundaries feels antithetical to a trans approach, yet one must also have design constraints to move forward. Always open to reconsideration.

Last year, I wrote about how important Loren Cameron’s work was to me and other transmasc folks.

Oliver Radcylffe’s memoir will be published later this year. Can’t wait.

Love this Kyle. I have a shelf in my house of API / API Queer authors for v similar reasons. It’s a great practice to be reminded that we exist and our stories are worth telling. Thank you for this list. Can’t wait to check out.

PS - I still have Grace Bonney’s beautiful In The Company of Women you gave me ❤️

The organization of this library is so pleasing to me