Writing from the road, again.

More accurately, writing while seated backward on the Northeast Regional rail corridor. The pre-spring, mostly leafless trees blur past my right. Look! Water! Boats! A lone fisherman is reeling in his line. Trucks! A Fanatics shipping warehouse! So. Many. Empty. Parking. Lots. Another bridge! Kids playing baseball. Blue skies. Thinking of you, President Biden, on Amtrak 140.

(To extend the metaphor, and because it is now quite late on a Sunday, consider this dispatch the first leg of a much longer journey…)

Headed back from a week in Washington, D.C., accompanying my girlfriend, artist

, on a big work trip.1 It was the longest I’ve spent in DC since moving away 20 years ago. My mom is a native Washingtonian. DC is where my family immigrated from Ireland in the early 1900s; her parents were first-generation Americans. DC was my first urban experience. Where my parents took me to big museums full of art, space, and history. Where I first met other kids with gay parents. Where I escaped to as a teen. Where I took a high school program for aspiring architects (two summers in a row). Where I snuck into gay bars, attended poetry slams, and first spoke at political rallies. Where I went to queer conferences in the early 1990s. Where I later moved as a baby adult after college and promptly made huge mistakes and hurt people I cared about. DC is where I spent a school year struggling to teach (flat out failing?) a room of third-graders. And then I fled and didn’t look back.It was nice to be back.

Thanks to a calendar coincidence, Higher Ground, Netflix, and a couple of good friends—we had the extraordinary opportunity to attend a screening of the new Rustin biopic at the White House.

We’d both seen the film before, and seeing ANY movie at the White House is remarkable, but witnessing strategist and civil rights hero Bayard Rustin’s tireless efforts to organize the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom while sitting in a building he was not welcome to enter—goosebumps.

On second viewing, I was struck by how much of the narrative tension of the film largely revolves around two things:

respectability (and therefore conformity) within political movements

the machinery of social activism

Rustin is less known than he should be. As once explained by writer Jelani Cobb, “Bayard Rustin is criminally under-recognized.”2 His role as a mentor and friend to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was often left to marginalia because of his sexuality. Unlike most at the time, Rustin was not ashamed of his queerness. Quite the opposite. In a clever, rhythmic montage, the film illustrates the impact of the rumors FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover set into motion speculating about “Dr. King and his queen.”3 Rustin was ultimately asked to step away from the movement for the good of the cause. It was the 1963 MOW and his operational genius that brought him back into the fold. And it took Dr. King going on television to defend his friend, for other leaders to let him stay.

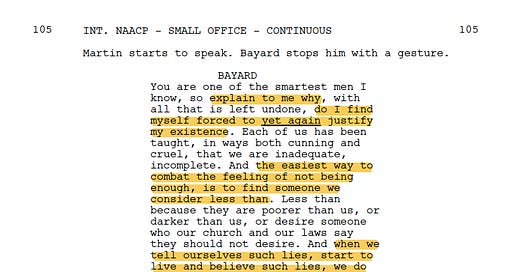

Rustin is often looked to as a hero of intersectional activism. Raised Quaker, he could not separate his activism into discrete categories; he believed in the rights for all of humanity. His ethos is beautifully dramatized in this poignant conversation with Dr. King that brought me to tears:

The film also brilliantly visualizes the hard labor of political and social change. It is work. A lot of work. Which requires people and all their human imperfections And time. Phone calls. Snacks. Garbage bins. Have logistics ever been more beautifully staged? Has reporting out the number of water trucks, chartered buses, and portable toilets ever been so successfully dramatized? They don’t call it “organizing” for nothing.

We chatted briefly with producer David Permut about his 14 years-long effort to bring Rustin’s story to the screen. (After years of pitching, he only got a yes when the Obamas started their own production company, Higher Ground.) Sitting in the White House, watching incredible actors bring life to a political demonstration behind the scenes, I wondered how the social activism of my/our lifetime will be remembered. And who will tell our stories? Which stories?

In August 1963, my white, conservative Irish Catholic grandfather piled his wife and six kids into a station wagon and drove to the Delaware shore to avoid whatever he feared would happen during the March. My mom was twelve.

Nearly 30 years later, my father took twelve-year-old me via Metro to Dupont Circle to experience the hundreds of thousands of people gathering for the 1993 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation. I can still hear the throngs chanting as we ascended, “We’re here. We’re queer. We’re riding on the escalator.”

I’m a little obsessed with the 1993 March. It was a BIG deal in my coming-of-age and also a huge milestone in LGBT movement history. The 1963 event set a record for the largest political demonstration in Washington, with over 250,000 people in attendance. Estimates vary, but the 1993 March is said to have had somewhere between 800,000–1M. And yet, I thought the 30th anniversary came and went last year without much discussion.

Running down an idea for an anniversary screening of J.E.B.’s documentary of the 1993 March on Washington, I got stuck on this fact I hadn’t noticed before: the name. The official title only included “Lesbian, Gay, and Bi.” Tucked into the Wikipedia page I read a note that including “transgender” in the name was put to a vote and failed to achieve a two-thirds majority. How did I miss this before? When was the vote? Who voted? I realized I know so little about how the march came together, about the drama that unfolded in the inner workings of the multi-year organizing effort.

Here’s what I do know by heart about the 1993 March on Washington:

President Clinton had just been inaugurated. The biggest policy issue was lifting the ban on gays in the military. Nancy Pelosi and Barney Frank spoke. The Indigo Girls and Melissa Etheridge sang. RuPaul strutted in stars and stripes. Comedian Lea DeLaria made everyone blush.

But until this week, I knew nothing about any trans representation. Chasing the thread to understand how and what and who, I learned only one openly trans person spoke: Phyllis Frye.

Phyllis Frye is an army vet, an activist, a lawyer, and a Texan. The following year, in 1994, the Houston Gay & Lesbian Caucus honored her with the Bayard Rustin Lifetime Achievement Award. And in 2010, she became the first openly transgender judge appointed in the United States. She served the City of Houston Municipal Courts until her retirement in 2023.

Here’s our first stop. On the next leg I’ll go a bit deeper into respectability politics in the LGBT movement and I’ll share some fun facts about the tunnels under the Library of Congress.

xx Kyle

Wendy gave an incredible lecture on the relationship between her work and photographer Dorothea Lange at the National Gallery of Art (West Building). Then she hosted hundreds of kids and adults at an epic, public DrawTogether Strangers gathering in the East Building’s atrium.

Hoover, meanwhile, continued to wield his power by attacking Blacks and gays despite there being speculation and some evidence to suggest he might have been both. My mom likes to remind me that DC was so small back then, that my father’s best friend was number three in the FBI leadership “underneath Director Hoover and his lover.”

I'll be honest, I'd heard of Rustin but knew nothing about him, much less that he was queer. Definitely going to need to check this movie out.